Two and a half decades in negotiations, the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway remains stalled on basic issues, with no clear way forward. The fate of the CKU is reflective of a host of issues that China’s Belt and Road Initiative faces as it tries to expand trade and travel infrastructure.

The China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway (CKU) has been under discussion for almost 25 years, but construction may never begin, The Third Pole writes in the article China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway remains uncertain. Despite numerous high level meetings the three countries have failed to reach a consensus on the route, railway tracks and sources of funding, as well as to address ecological, geopolitical and national security concerns.

In his resignation speech on 16 October 2020, the then Kyrgyz President, Sooronbay Jeenbekov, shared his dream for the railway. “One of my dreams was the realisation of the CKU railway. High-level negotiations took place, and a political decision was taken regarding the start of the work. Kyrgyzstan needs this like it needs air and water, and I hope that my countrymen who have come to power will continue with it and make it a reality”.

Conflicting interests

The three countries have conflicting interests. China and Uzbekistan want a shorter and cheaper transit route to Europe and the Middle East, whereas Kyrgyzstan prefers a longer variant that will connect centres in the north and south of the country and boost its economy. The train is expected to carry consumer goods from China to Central Asia and take food produce and minerals from Kyrgyzstan back to China. Uzbekistan hopes to boost its oil and cotton exports. At a meeting about the development of the Kyrgyz rail industry in June 2020, the then President Jeenbekov noted the importance of railways for the country, the largest and most strategically important projects in this regard is the CKU. The next day, general director of the Kyrgyz Railway Company, Vasily Dashkov, hastened to inform journalists that documents relating to the construction of the CKU were ready and denied there was any disagreement over the route and the track.

In an interview with “Birinchi Radio”, Jeenbekov called the construction of the route vitally important, and added that a 3+1 agreement was reached with Russia for participation in the project. “When the pandemic began and borders were closed, we found ourselves in a very bad situation. Our priorities weren’t only the economy, but the issue of providing food and flour to people. We were again convinced that the railway is very important for us. The Chinese are interested in this project.”

A dead end?

In an interview with MK-Asia, former Kyrgyz deputy Minister of Transport and Communication Ulan Uezbaev underlined that although there has been a political decision to build the railroad, as of yet no viable approach has been suggested. “There’s no investment or decision about a partnership between the government and private sector. After a feasibility study, the first variant of the railroad cost USD 1.5 billion – during discussions this sum rose to USD 4.5 billion, a figure which will continue to grow in the coming 5 years of discussion until it reaches around USD 8 billion. Construction on this project must begin now.”

According to the Kyrgyz Railway Company (Kyrgyz Temir Zholy), the idea of the CKU railroad first appeared in 1996 when China announced the start of construction of a South Xinjiang rail route from Korla to Kashgar. A year later, China, Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan signed a memorandum in Tashkent and Bishkek to cooperate on the construction of a Kashgar–Osh–Andijan railroad, and published the minutes of the first meeting of the Joint Working Commission.

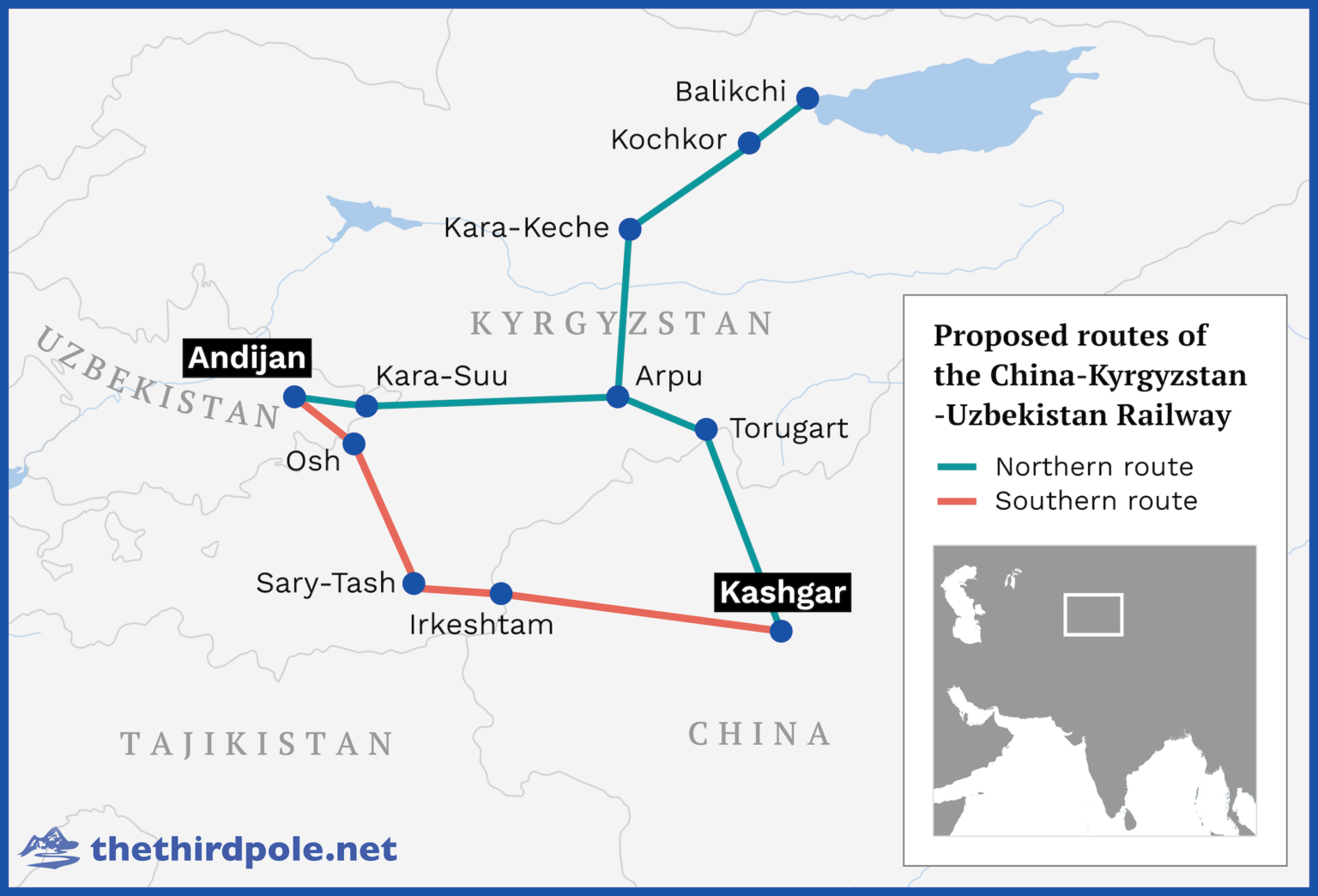

Initially, experts from the three countries researched eight options for the route, but eventually settled on two. A northern route from Kashgar to Andijan would go through Torugart, Arpu and Kara-Suu, and a southern route would go through Irkeshtam, Sary-Tash and Osh. In 2002, the Chinese government gave Kyrgyzstan a 20-million-yuan technical grant for research on the main line, after which the two sides agreed on the northern route, though the southern option was more beneficial for China.

Impasse over routes

The northern route is 270 kilometres long and will link the northern and southern railways of Kyrgyzstan via an internal route of Balikchi – Kochkor – Kara-Keche – Arpa – Kara Suu. This will allow Kyrgyzstan to provide an inter-regional rail system. However, the Chinese government representatives rejected the Kyrgyz proposal during an online meeting on 15 July 2020 indicating that the railway width and route must be agreed by all sides.

Whether the Kyrgyz government’s call for the northern route will materialise is unclear but it has come under criticism from some Uzbek experts. Bakhtiyor Ergashev, director of the Tashkent based think-tank “Mano” believes that the Kyrgyz authorities are focusing on purely “selfish interests” by proposing the northern route. “The option that they [Kyrgyz government] offer is simply longer and more expensive and does not work for the idea of a fast and affordable railway construction,” Ergashev told a news website in Kazakhstan.

Technical challenges

Preliminary data from feasibility studies show that construction will take place in mountainous areas. This will involve building 48 tunnels over almost 50 kilometres. This includes a Ferghana Tunnel (14.1 kilometres), a Torugart tunnel (3.4 kilometres) and a Kurshab tunnel (1.7 kilometres). Large engineering structures such as bridges, railway divisions and transfer stations will also have to be built. There are also technical problems linking the new railway with existing regional rail routes. An official from the Kyrgyz Ministry of Transport and Communication told The Third Pole on condition of anonymity that “the width of the track gauges is different in Kyrgyzstan and China. So in the Tuz-Bel Pass in Kyrgyzstan, Kyrgyzstan insists on building a station where carriages will change tracks, and there’ll be cargo weighing, organisation of the trains and sorting of the containers”. This will add both time and cost to transporting goods.

In his opinion, it would be better to build a station on Uzbek territory so that they can deliver goods there directly, by passing the need for a transition station. “But this doesn’t suit the Kyrgyz side. Even if the Chinese side will compromise, then their government, considering that they’re ready to invest billions in this ambitious project, will want to claim mining rights as a form of collateral”.

Mining the price

Kyrgyzstan is rich in mineral deposits, in particular gold, which China wants to exploit. More than ten years ago the Kyrgyz government offered to pay China for building the railroad with rights for gold mining, the official said. It is unclear if that offer still holds, but the former Kyrgyz Minister of Transportation Janat Beishenov told a local newspaper in Kyrgyzstan that there are 23 mineral deposits, including: coal, lignite, gold, aluminum, iron, gypsum, barite, lead, terandite, shell limestone, construction limestone and other can be respectively developed along the railway route if CKU project moves forward.

Environmental impacts

Experts worry about the environmental damage of building a railway through fragile mountain regions. Kyrgyz Prime Minister’s advisor and economist Kubat Rahimov said that “any infrastructure project will need additional measures relating to explosive-technical and drilling operations requiring hundreds of thousands or even millions or cubic metres of rocks to be moved, as well as building tunnels, bridges, railway stations, loading and unloading stations, and all kinds of junctions, bypasses and additional tracks.”

The CKU railroad project is particularly difficult, said Kubat Rahimov, because it will require building tunnels through mountainous areas. Regardless of the route, the environmental consequences will be significant, as in certain areas it will be necessary to change the course of rivers and change drainage patterns, because we will need to build bridges with columns and engineering structures which will be directly on the water surface.

“Experience demonstrates that the building of a mountainous railroad in Tibet required changing the course of local rivers and putting concrete pillars in areas where water once flowed. This inevitably affected flora and fauna. The seismicity of the territory also affects the project– introducing the necessity for load-bearing steel-concrete structures, additional engineering measures, additional concrete works, the strengthening or filling of cracks and joints, all of which will affect rocks. In certain areas dams will need to be built to join two mountains that are separated by a narrow gorge or river. This negatively affects seismicity: if the railroad goes through in an area with tectonic faults or where there’s a likelihood of landslide or rockfall. The technogenic activity will have a negative impact in any case.”

An expert in the field of environmental protection and climate change from Bishkek, Vladimir Grebnev, warned the environmental costs of the project are likely high. “But this shouldn’t be said without any proof. As international legislation states, there must be an EIA (Environmental Impact Assessment) with the involvement of society and appropriate consultants,” he said.

However, there is weak enforcement of environmental protections around infrastructure and mining major projects in Kyrgyzstan. The development of the Kumtor gold mine – one of the highest gold deposits in the world in the Issyk-Kul region – has led to the melting of the Davydov glacier in the Tianshan mountains. Mining waste was not properly stored, resulting in melting snow and polluted lakes and rivers.

According to Jamal Sooronkulov, the railroad may spur the development of nearby mineral deposits, which again will have negative environmental impacts. Therefore, in realising this ambitious project, a parallel project for the protection of the environment must also be provided.

However, some scientists say the benefits outweigh the costs. Kamil Ashimov, the director of the Jalal-Abad region Science Centre of the Kyrgyz Republic’s Academy of Science. “Kyrgyzstan’s ecology won’t be impacted at all by the construction of this CKU railroad. During the work, there will be minimal harm to biodiversity, but, in contrast to road freight transport, the operation of the railroad is considered much less dangerous,” he said.

The exhaust emissions of road freight vehicles are more environmentally damaging than rail transport. Therefore, constant monitoring of the loaded trains will suffice.

However, the array of problems and lack of cooperation from the Chinese side may force Kyrgyzstan to reject this idea outright. There is an option that if the Kyrgyz side continues to delay this question, then China will find another way to build a road through neighbouring Tajikistan (Gorny Badakhshan), thereby bypassing Kyrgyzstan. And then Kyrgyzstan will be at a loss.