Italian leaders have developed a dangerous preoccupation with being seen to oppose the rest of Europe – particularly Germany – and wild ideas about a future close relationship with China, European Council of Foreign Relations reports in its article Italy's industrial geopolitics: Torn between Europe and China. Germany’s relative success at containing the coronavirus has meant that companies there have not had to stop trading completely – and they are now asking their Italian suppliers to restart operations.

This has put the onus on Italian firms, and on the Italian government, to navigate between the competing demands of healthcare and the need to reboot the economy. But, in Rome, political leaders are putting the recovery in danger by lacking a strategic vision and by focusing more on collaboration with China than with the rest of Europe.

The powerful Federation of German Industries and the three main associations of the German mechanical industry have called for Italian firms to resume activity in a coordinated manner, effectively lifting the production blockade. Italian companies – especially those in northern Italy, the country’s manufacturing heartland – are indeed asking for decisive and immediate support to return to business as soon as possible. Carlo Bonomi, the new president of Confindustria, Italy’s most powerful industrial organisation, has emphasised the need for this by accusing the government of slowness, poor preparation, and failure to understand industrial policies and the importance of international value chains.

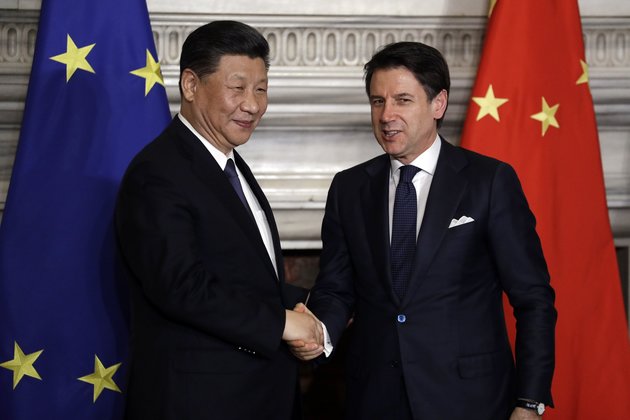

These actors have good reason to be worried. A new strain of rhetoric has become increasingly prominent in Italian politics in recent months: many public debates and analyses depict China as counterbalancing a malevolent Europe. Politicians from the Five Star Movement and the opposition League promote a narrative in which China is a growing economic partner for Italy. And China itself has been busy exploiting the current crisis to project a friendly image beyond its own borders and to maximise opportunities for its own economy. Recent polls show this has been a successful campaign, as Italians consider China to be their top “friend” in the world. Germany and France top the polls for “enemy” countries.

The populists’ anti-European rhetoric has already had an impact: the Italian government refused to accept €39 billion of EU aid from the European Stability Mechanism that could have quickly helped Italy, after Five Star Movement politicians expressed fear about a Troika-like control mechanism. Now, negotiations have started that will delay the arrival of the funds and delay the recovery of Italy’s economy. The picture is complex, however. The negative rhetoric reached such a height that even the Five Star Movement’s Luigi Di Maio – who serves as foreign minister and who has previously advocated a gradual shift towards China – has recently felt compelled to issue a reassuring statement about Italy’s positioning: “we have strengthened our relationships with a strategic commercial partner such as China, but this will not change our geostrategic alliances.”

The massive Chinese market is unlikely to make up for Europe’s high-value, integrated market. And big-ticket projects such as those China has deployed around the world in the past decade – buying up infrastructure and bringing direct investment to countries – will hardly match the weight of the single market. If China can be no substitute for Germany and the rest of Europe, Italy’s economic interests remain with the continent – especially in the short term, while no quick fix with Beijing is available. Due to Italian leaders’ preoccupation with being seen to oppose the rest of Europe – particularly Germany – and their wild ideas about a future close relationship with China, reopening supply chains between Italy and Germany has not seemed to be a political priority during the lockdown.

This comes at a potentially dangerous time for Italy – fractures in the international system created by the US-China decoupling could cause Italy and its export-dependent economy to fall between the cracks. Economic interdependence has been under pressure for several years, not least since US President Donald Trump launched his trade war, with the stated aim of – among other things – bringing factory jobs back to American soil. In addition, growing competition for geo-economic and technological primacy between Washington and Beijing has led political leaders across the globe to regard industrial production capacity as a strategic asset. The current crisis has broadened the industrial categories that states define as strategic, to include critical raw materials and key technological inputs, such as semiconductors. In the short term, this new reality might lead the United States to seek greater control over these sectors, limiting China’s influence over – and, potentially, access to – them.

In a world in which trade depends on geopolitical shifts, the capacity to produce strategic goods has proved to be essential. Unfortunately, in recent weeks, it has become clear how important it is to be able to produce medical equipment such as masks, ventilators, and reagents needed for testing. In the near future, the same could happen to the supply chain of raw materials or semi-finished products of high technological value. The European Union noticed these global changes even before the crisis, highlighting how it was necessary to bring more manufacturing back to Europe in some sectors. It is no coincidence that industrial policy was already central to the thinking of the new European Commission, which published on 10 March an industrial strategy that focused on innovation, unfair competition, and the need to restore production capacity in Europe.

The lockdown has interrupted industrial production in Italy and led to only a cautious reopening of the economy. At a moment when countries’ relative industrial strengths look to set to undergo great shifts, the coronavirus crisis threatens to cut Italy out of the European supply chains in which its industry plays a vital part. Italian leaders may be content to play politics with citizens’ jobs for the moment. But those at risk of unemployment may take a dim view of this at the next election. Loose but persistent talk blaming Europe and Germany for all ills could, however, mean that voters still blame Brussels for their problems. As such, the need to reopen Italy’s economy should be a question that draws the attention of leaders across Europe. The post-coronavirus reality shows that, at a time when globalisation is increasingly vulnerable, European countries are bound together not only by common political values but also by the strength of their industrial interdependence.