Known for its pristine Aegean beaches and architectural wonders, Turkey also draws tourists for its cosmetic treatments. Affordable prices, visa free entry and short flight distances from much of West Asia, North Africa and Europe, all add to the appeal of visiting Turkey to get medical and cosmetic procedures done.

Middle East Eye reports that Flights back from the Turkish city to Western Europe or the United States are often full people bandaged up, avoiding eye contact with fellow travellers. Fillers, botox treatments and rhinoplasties are also popular procedures for tourists looking to change their appearance. The country is a top ten destination for medical tourism globally, with 600 registered clinics in Istanbul alone, according to Patients Beyond Borders (PBB), an organisation that surveys medical tourism. According to local media reports, more than 100,000 people visit the country for hair transplant procedures alone, the vast majority from Arab states.

The importance of cost

“People can find quality service at affordable prices and work with surgeons and technicians who know the job well,” Ekram Caymaz tells Middle East Eye, succinctly explaining the appeal of “getting work done” in Turkey. A leading clinician in hair transplantation at Istanbul’s Hair Upload clinic, Caymaz says patients are drawn to Turkey for its comprehensive approach to customer care. For example, most clinics will not offer the surgery alone but as a package deal, which can include everything from flights, transfers, luxury accommodation, regular aftercare and even tours of the city. “The hair transplant industry is not only about the surgery, but also about meeting the customer from the airport, arranging the hotel, and following up professionally until the first check-up,” Caymaz says.

For the customer that means every aspect of the procedure is taken care of - they simply need to turn up. Prices are another draw, with Caymaz charging between $4,000 and $6,000 for his hair transplant procedure, which is considered cheap. Others can be as low as just over $1,000, though the quality of service inevitably varies wildly. In comparison, procedures such as hair transplants are not available for free on the UK's National Health Service (NHS) and can cost as much as £30,000 ($36,700) when done privately. Similarly, cosmetic rhinoplasties can cost around £7,000 in Britain ($8,570), not including the cost of consultations and follow ups, whereas in Turkey the procedure costs less than half that. Key overheads, such as staff salaries, are much lower in Turkey than in Western Europe or the US, while standards of medical training are relatively high compared to other countries in the Middle East or Asia. Turkey’s ongoing economic crisis has also helped depress prices to a degree that keeps them affordable for Europeans.

Speed of treatment

But price is not the sole reason for the popularity of cosmetic and other procedures in Turkey. Speed of treatment is another factor, albeit one that serves as something of a double-edged sword. Weight loss surgeries, for example, are only available on the NHS in extreme cases, for people who have a body mass index of 40 or more, meaning they are severely obese. Before proceeding, patients must agree to a rigorous long term follow-up after the surgery, including making healthy lifestyle changes and regular check-ups. Even for people who are eligible, the wait for treatment can last years.

Emre Atceken, the co-founder and CEO of WeCure, a UK-based medical facilitation company that specialises in cosmetic procedures, says patients are often eager to have their procedure done sooner rather than later, spurring them to book appointments abroad. “Here in the UK, almost six million people are on the waiting list for non-urgent hospital treatments and procedures according to the latest NHS statistics,” he tells Middle East Eye. “It’s all too common a story for us to hear of someone we know having to wait over six months for a crucial operation, whereas if you go to Turkey, on average, it would be between two to four weeks.” Most clinics in Turkey offer over the phone or video consultations, meaning patients can be seen, and make their decision about their surgery without even having to travel abroad.

Safety and the black market

Some experts, though, have warned that patients in search of quick and affordable solutions could be setting themselves up for trouble further down the line. Cosmetic dentist Sam Jethwa, from the UK-based Perfect Smile Studios, tells Middle East Eye that patients can easily be misled when it comes to cosmetic procedures. “Getting a dental procedure abroad means you risk not having any legal protection, which can leave patients with difficulties afterwards,” he says, adding that patients can also be misinformed, resulting in needing further treatment or repeat procedures. “The need to have corrective work done back in the UK due to botched cosmetic dentistry procedures (abroad) is on the rise," Jethwa says. “We see these patients attending our clinic afterwards regularly, sadly after patients have already chosen treatments that they were not fully appreciative of the risks of.”

While there is no suggestion that a typical procedure in Turkey will result in problems for patients, there are those looking to capitalise on the trend and exploit vulnerable patients. The International Society for Hair Restoration Surgery (ISHRS), a global non-profit medical association active in over 70 countries, has launched a campaign named Fight the Fight in an effort to shed light on the dangers of the "medical black market" and medical tourism package deals. Launched in 2019 in response to the growing number of people going to unlicensed technicians to get hair surgeries, the organisation offers support to victims of treatments that have gone wrong and provides education and training about the subject. ISHRS says there have been cases where doctors or those purporting to have medical training have misled patients and carried out illegal practices, resulting in injuries, scarring and the depleted or uneven appearance of hair.

Caymaz reiterates that the onus to make an informed decision lies with the patient. “Although clinics and hospitals are inspected, there are so called ‘under the stairs’ places, which are much cheaper,” he says. “It is very important to examine their social media and videos, the words they say and what is written must match up.” According to the doctor, one of the main issues within the industry is the lack of follow-up after the operation to ensure there are no complications. “This is a very important detail, and most clinics in Istanbul do not follow up after the operation. Even customers who have had operations in other clinics ask us about this,” Caymaz says.

According to a recent report in The Times, cheaper prices and lax regulation abroad have left people with botched results. Christopher D’Souza, president of the British Association of Hair Restoration Surgery (BAHRS), places some of the responsibility for those failed procedures on unethical marketing tactics by clinics based in Turkey. “Package deals are often advertised with unlimited amounts of grafts and are time limited, which pressurises patients to make a decision. This goes against the advice of doctors in the UK,” he says. “I have operated on many repair cases where patients report that although they felt something was not quite right when they were in Turkey, having already invested themselves, their time and their money so far, they succumb to the notion of, ‘I am sure it will be fine’, and this is not acceptable,” D'Souza says.

Social media and medical tourism

Anyone likely to have mentioned hair loss, weight gain or insecurity about their looks online is likely to have been bombarded with Instagram or Google adverts promising affordable and sometimes miraculous solutions to their issues. Part of the reason for the popularity of medical and cosmetic tourism is social media advertising. This trend is compounded by entertainment news coverage of celebrities going public about their own procedures.

Hair transplants are very popular among footballers, with Wayne Rooney confirming he had one in 2011 and Emirati singer Hussain Al Jassmi putting his dramatic weight loss down to a gastric bypass in 2010.

Selena Marianova, a UK based 22-year-old social media content creator and clinic owner, says that social media has an "undeniable influence" on individuals considering surgical enhancements. In a YouTube video, viewed over 300,000 times, Marianova recounts her experience to her followers. She says that she wants to help other people by sharing information, and that she chose Turkey for her surgery because of their advanced medical technology and experienced doctors. Marianova went to Istanbul for a rhinoplasty in 2019, cautioning, however, that young people need to feel confident in who they are before they proceed with any surgical enhancements. “Plastic surgery isn’t to be taken lightheartedly,” she says. “Being a content creator, it is extremely hard to not pinpoint parts of myself that would need ‘improvement’ because I am constantly looking at myself in videos, photos and in the mirror, which can be very mentally draining for people who do not have a strong self concept.”

The link between social media use and negative self-image is well established by researchers but for all the ethical considerations, the bottom line is that cosmetic surgery is big business for Turkey. In 2018, the cosmetic enhancement industry was worth $2bn in Turkey and hair transplants alone are now a billion dollar industry.

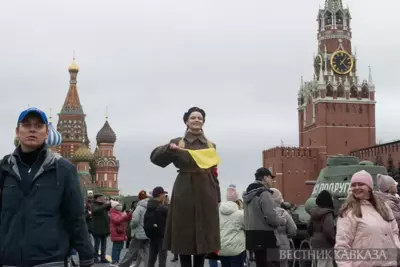

Those valuations are likely to have increased in the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic, with a surge in interest in cosmetic surgery globally. Despite the concerns, Turkey’s health and cosmetic surgery industries are winning tickets in a country otherwise suffering economically. The throngs of red scalped men in Istanbul’s public squares and bandaged noses in its metro stations are therefore unlikely to disappear anytime soon.