These days, Russia is the 12th largest tomato producer in the world. While that’s fairly far down the list, tomatoes are extremely popular in Russia, and are grown in almost 90 percent of home gardens. They’re a vital ingredient in soups, stews, and sauces, and pickled tomatoes are eaten throughout the year, Atlas Obscura writes in the article Why Soviet Russia Named a Tomato After an American Celebrity. Many Russian tomatoes have evocative names. There’s the Mother Russia and the Black Sea Man. But perhaps the most unusual of all is the Paul Robeson tomato. Named after the African-American singer, actor, and activist, his namesake tomato has become a cult favorite in American gardens.

Born in 1898, Robeson was born to a once-enslaved father and a mother from a Quaker family. While attending Rutgers University, he won 15 varsity letters in a variety of sports and graduated as valedictorian of his class. At Columbia Law School, he met his future wife, Eslanda “Essie” Goode, who convinced him to try acting. (Robeson was already well-known throughout New York’s black community for his singing voice.) In the end, Robeson only practiced law briefly, quitting his firm when a white secretary refused to take dictation from him.

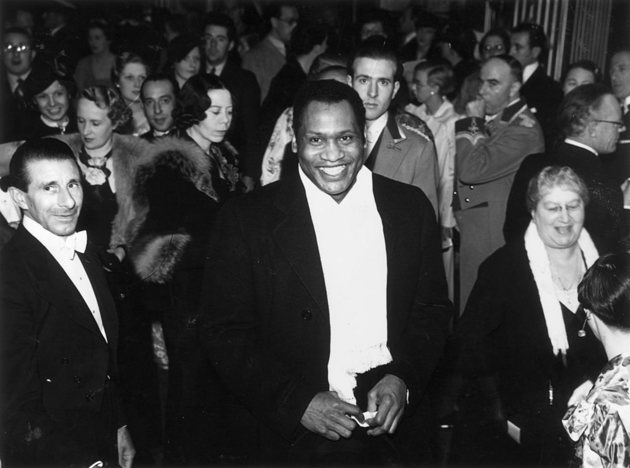

While still in school, he played his first role, as the lead in the play Simon of Cyrene. Then, in 1924, he played the lead role in Eugene O’Neill’s play All God’s Chillun Got Wings, which led to other lead roles in Othello and The Emperor Jones. However, Robeson may be best known for his rendition of “Ol’ Man River” in the musical Show Boat, which he performed onstage and on film. As he found fame and fortune, Robeson became increasingly interested in the rights of workers, particularly those of southern blacks. Soon, he found himself sympathizing with Communist causes throughout the world. When Robeson traveled to Moscow in 1934, he said, “Here I am not a Negro but a human being for the first time in my life.”

In the Soviet Union, he was received by adoring and respectful crowds. Soviet leader Joseph Stalin even marketed the Soviet Union as a place of opportunity and equality for African-Americans. Ultimately, around 18,000 African-Americans traveled there in the 1930s. By the 1940s, Robeson became active politically. He espoused that unions were crucial to civil rights, and condemned discrimination and violence against African-Americans. His affiliation with both the Civil Rights Congress and the Council on African Affairs made him a target for the House Un-American Activities Committee.

In 1950, the State Department denied Robeson a passport, stating that “his frequent criticism of the treatment of blacks in the US should not be aired in foreign countries.” Robeson testified before Congress again in 1956, after he would not sign an affidavit saying that he was not a Communist. When asked why he had not remained in the Soviet Union, he replied, “because my father was a slave and my people died to build the United States and I am going to stay here, and have a part of it just like you.”

Despite his bravery, Robeson’s efforts took their toll. His later years were marked by bipolar depression and suicide attempts. His son believed both were due to years of government harassment and surveillance. After years of seclusion, Robeson died at age 77 in 1976.

Less than two decades later, Kent Whealy, the co-founder of Seed Savers Exchange and an advocate for organic agriculture and saving heirloom seeds, met Marina Danilenko, the owner of the first private seed company in Moscow, who purchased seeds from a network of farms and eventually sold approximately 500,000 packets through the mail to Russian gardeners. After learning about her company, he arranged for her to visit the United States for mentorship (as most Russians did not know how to operate a business after the collapse of the Soviet Union). In 1992, Danilenko visited Southern Exposure Seed Exchange in Mineral, Virginia, for three days to learn about the operation of a seed company. In return, over the course of two visits to the United States, Danilenko donated 170 varieties of Russian tomatoes to the Seed Savers Exchange—including a tomato called the “Pol Robeson.” In turn, Jeff McCormack, founder of the Southern Exposure Seed Exchange, introduced the tomato to the American public via their catalog.

Although it is unknown who developed or named this tomato, it can be easily surmised that the name derives from its color once it ripens. The Paul Robeson is a brick red tomato that often takes on a black hue. In Danilenko’s words to McCormack, “the more the summer, the more the black color.” But the moniker is also a tribute. Both seed catalogs and those lucky enough to have tried it have described it as sweet, smoky, complex, and tangy.

Even as he was denounced in the United States, Robeson remained beloved in Russia. In 1952 he received the Stalin Prize, which was the highest honorary distinction in the country, and in 1964, an article in the Russian magazine Krugozor stated, “Whoever heard Paul Robson at least once will not forget his voice. We know well this big man with the eyes of a wiseacre and the smile of a child, a great singer and a courageous citizen, whose name has become a symbol of a freedom fighter.”

Although he was often vilified in life by his government, Robeson’s artistic and civil rights work has resonated long after his death. That everyone, regardless of race or creed, can enjoy the Paul Robeson tomato is the ideal testament to his legacy