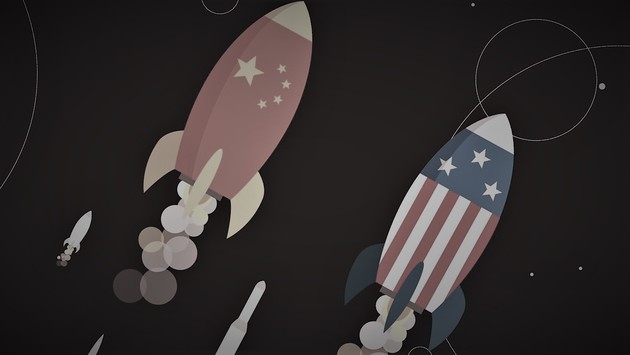

China and the US are in a next generation space race, and this time the ultimate prize isn’t just reaching the moon. Both powers regard space as the next theatre of international security – and that has worrying consequences for the UK and the world. CapX reports that on 17th June, a crew of Chinese astronauts landed on the core module of a space station that will be completed in 2022.

Meanwhile NASA’s Artemis Programme aims to create a sustainable crewed presence on the moon and in orbit, and the US established an armed Space Force in 2019. Although Beijing has never revealed an open interest in competing with other countries in space, and, in fact, sought to become a partner in the International Space Station (ISS), its growing technological dominance has not gone unnoticed in Washington.

Aside from the risk of cyber, and even violent warfare blasting into orbit, analysts have identified two further emerging risks associated with the new space race. The first is a security risk resulting from Chinese state involvement in global broadband. The second is the danger of collisions or natural disasters caused by space debris, or unfettered activity in extra-terrestrial locations of particular scientific interest.

SpaceX and China’s major state-owned enterprises are competing to roll-out of ‘mega constellations’ of satellites to provide broadband coverage. These work by transferring data between users and conduits on the ground, but in the future links between satellites will enhance bandwidth and increase connection speed. SpaceX is currently the dominant player in this market, having launched more 1,300 satellites into low earth orbit. But China has responded with plans for a constellation numbering upwards of 10,000 satellites.

The connection to the Chinese state could prove fraught in the long run, especially if, as can be readily imagined, Chinese entities start to battle US firms for users. A push-back, similar to the one against Huawei’s 5G technology, may further contribute to polarisation as countries, especially in the developing world, are pressed to choose sides.

Further, the uncontrolled and competitive expansion of mega-constellations increases the risk of generating space debris. In a climate of geopolitical and commercial competition, actors on both sides are less likely to coordinate, share information and conduct joint risk assessments. Firms may cut corners when it comes to maintenance and ensuring the safe removal of satellites in case of failure. Insufficient coordination will make it much more likely that satellites crash into each other in low earth orbit.

Coordination failure may also increase the risk of a serious incident somewhere like the Lunar South Pole, where many scientific projects could be taking place at the same time. Vibrations and the generation of lunar dust during take-off and landing of spacecraft on the lunar surface, for instance, may disrupt nearby missions and even trigger lunar avalanches. Lunar dust could further impede measurements by covering scientific instruments. Given that both the US and China aim to establish crewed presence on the moon and in orbit, it is alarming that existing frameworks of norms, such as the Outer Space Treaty, lack appropriate and detailed mechanisms to coordinate these competing interests in space. While the US has promoted the Artemis Accords, which include the establishment of safety zones to mitigate risk, Beijing is not signed up.

Although China’s moon landing is not scheduled until the mid-2030s, thus posing little risk of interference with current US plans in the medium-term, that doesn’t mean the risk of clashing lunar missions is eliminated, just delayed. In the context of the obvious risks of cyber and active warfare in space, it’s imperative for stakeholders to develop adequate legal and policy frameworks to mitigate possible disruption to satellites used for civilian purposes.

The UK may also benefit from increased funding for NASA’s Artemis programme. Any renewed race to the moon will require the US Congress to channel additional funding to NASA. As a member of the European Space Agency (ESA), which in turn is a key partner of Artemis, the UK is set to at least benefit indirectly from such budgetary and policy developments. For instance, SSTL, a UK-based satellite manufacturer, is already developing a lunar navigation and communications system. If the UK manages to position itself well within the ESA, it should benefit from growing lunar activity.

Rather than burying its head in the sand when it comes to the risks of the new space race, the UK should look to the stars and use its commercial clout and diplomatic influence to make sure the right side wins.