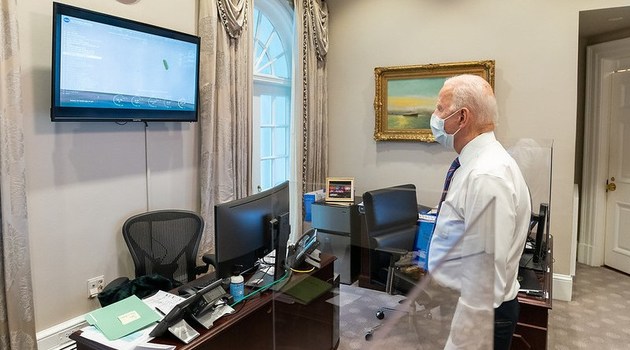

A much-anticipated foreign policy move by the US Biden administration on how to counter China’s unhindered economic growth and political ambitions came in the form of a virtual summit on Friday, linking America with India, Australia and Japan, Eurasia Review reports. Although the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue — known as the “Quad” — revealed nothing new in its joint statement, the leaders of these four countries spoke about the “historic” meeting, which was described by The Diplomat website as “a significant milestone in the evolution of the grouping.”

However, the joint statement contained little of substance and certainly nothing new by way of a blueprint on how to reverse — or even slow down — Beijing’s geopolitical successes, growing military confidence and increasing presence in and around global strategic waterways. For years, the Quad has been busy formulating a unified China strategy, but it has failed to devise anything of practical significance.

The Quad began in 2007 and, after an eight-year hiatus, was revived in 2017 with the obvious aim of repulsing China’s advancement in all fields. Like most American alliances, the Quad is the political manifestation of a military alliance, namely the Malabar naval exercises. These started in 1992 as a bilateral US-India exercise but soon expanded to include all four countries.

Since Washington’s “pivot to Asia” — the reversal of established US foreign policy, which was predicated on placing greater focus on the Middle East — under Barack Obama, there is little evidence that its confrontational policies have weakened Beijing’s presence, trade or diplomacy throughout the continent. Aside from some close encounters between the American and Chinese navies in the South China Sea, there is very little to report.

While much media coverage has focused on America’s pivot to Asia, little has been said about China’s pivot to the Middle East, which has been far more successful as an economic and political endeavor than the American geostrategic shift.

The American seismic change in its foreign policy priorities stemmed from its failure to translate the Iraq invasion of 2003 into a decipherable geoeconomic success, despite seizing control of Iraq’s oil — the world’s fifth-largest proven reserves. The US strategy proved to be a complete blunder.

Financial Times Asia Editor Jamil Anderlini raised a fascinating point in an article last September. “If oil and influence were the prizes, then it seems China, not America, has ultimately won the Iraq war and its aftermath — without ever firing a shot,” he wrote. Not only is China now Iraq’s biggest trading partner, but Beijing’s massive economic and political influence in the Middle East is a triumph. China is now, according to the Financial Times, the Middle East’s biggest foreign investor and a strategic partner for all Gulf states save Bahrain. This can be contrasted with Washington’s confused foreign policy agenda in the region, its unprecedented indecisiveness, the absence of a definable political doctrine, and the systematic breakdown of its regional alliances.

This paradigm becomes clearer and more convincing when understood on a global scale. By the end of 2019, China had become the world’s leader in terms of diplomacy, as it boasted 276 diplomatic posts, including many consulates. Unlike embassies, consulates play a more significant role in terms of trade and economic exchanges. According to the 2019 figures published in Foreign Affairs magazine, China had 96 consulates compared with America’s 88. As recently as 2012, Beijing had lagged 23 posts behind Washington’s diplomatic representation.

Wherever China is diplomatically present, economic development follows. Unlike America’s disjointed global strategy, China’s ambitions are articulated through a massive network known as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). When completed, the BRI will unify more than 60 countries around Chinese-led economic strategies and trade routes. To help this materialize, Beijing has moved to establish closer physical proximity to the world’s most strategic waterways, heavily investing in some and even establishing its first overseas military base in Djibouti overlooking the Bab Al-Mandab Strait.

At a time when the US economy is faltering and its European allies are politically fractured, it is difficult to imagine that any American plan to counter China’s influence, whether in the Middle East, Asia or anywhere else, will have much success.

The biggest hindrance to Washington’s China strategy is that there can never be an outcome in which the US achieves a clear and precise victory. Economically, Beijing is now driving global growth, thus balancing out the international crisis resulting from the coronavirus pandemic. Hurting China economically would weaken the US, as well as the global markets.

The same is true politically and strategically. In the case of the Middle East, America’s pivot to Asia has backfired on multiple fronts. It has registered no palpable successes in Asia, while also creating a vacuum in the Middle East for China to fill.

Some wrongly argue that China’s entire political strategy is predicated on its desire to merely “do business.” While economic dominance is historically the main driver of all superpowers, Beijing’s quest for global supremacy is hardly confined to finance. On many fronts, it has already either taken the lead or is approaching the front. For example, China and Russia last week signed an agreement to construct an International Lunar Research Station. Considering Russia’s long track record in space exploration and China’s recent achievements in the field — including landing the first ever spacecraft on the South Pole-Aitken Basin area of the moon — these two countries look set to take the lead in the resurrected space race.

The US-led Quad meeting was neither historic nor a game changer, as all indicators attest that China’s global leadership will continue unhindered. This is a consequential event that is already reordering the world’s geopolitical paradigms, which have been in place for more than a century.