It fires missiles that travel at 2km per second and can hit targets flying twice as fast. It can target 80 different enemy aircraft, drones and cruise missiles at the same time from 400km away, and spot stealth warplanes that previously evaded detection. But, as Financial Times writes in an article "Russian sanctions: why ‘isolation is impossible’" arguably the most dangerous aspect of Russia’s S-400 Triumph missile defence system is the damage it has inflicted on the clout of Washington’s anti-Moscow sanctions programme, and concerted efforts by the US to isolate Russia from the rest of the world.

Despite sweeping sanctions against Russia’s defence industry to shut down its lucrative exports and a ban on other countries buying the S-400 specifically, Russia is doing a roaring trade in what most experts consider the world’s most advanced air defence system.

Over the past year, Turkey and India have signed deals to buy S-400s, China has received its first deliveries, and Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Iraq have begun negotiations over deals to acquire the sanctioned systems.

If the west’s sanctions regime, first introduced in March 2014, was designed to cut off Moscow from the rest of the world and isolate its critical industries, the truck-mounted missile launchers are a $400m-a-piece example of how that effort has failed.

“There is no question about the isolation of Russia. Nobody is even talking about it,” says Andrei Frolov, editor-in-chief of Russia’s Arms Export journal. “There are major breakthroughs thanks to China and India . . . the message is that Russia is still open for business.”

If the measures were designed to make Moscow an international pariah, friendless and toxic, they are falling short of achieving their goal.

An ever-closer friendship with China has provided Moscow with international finance, new trade opportunities and diplomatic heft. Moscow has also deepened its ties with a host of countries in the Middle East, from Turkey to Israel, Saudi Arabia to Iran, expanding its influence in the region at a time of American hesitation.

At the same time, a steady stream of EU leaders visiting the Kremlin, foreign direct investment from European corporates and continued demand for Russia’s oil and gas exports belie the rhetoric of belligerence from Brussels.

“Isolation is impossible, that is clear,” says Andrei Bystritsky, chairman of the Valdai Discussion Club, a Russian think-tank. “It was possible, 30 years ago, in the Soviet times. Then there were just two blocs. But now there are so many options.”

When it comes to Russian isolation, reality has not matched rhetoric. While major defence deals like the S-400 agreements have drawn the ire of Washington, all of the EU’s biggest economies have quietly continued to do business with their eastern neighbour.

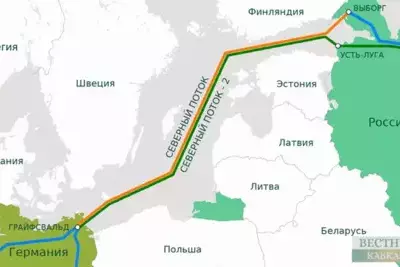

Berlin, a key supporter of sanctions, steadfastly supports Nord Stream 2, a Russian gas pipeline being laid under the Baltic Sea that opponents say will only increase Moscow’s influence over Europe’s energy supplies.

French president Emmanuel Macron was Mr Putin’s special guest at the annual St Petersburg Economic Forum earlier this year, telling his host: “Dear Vladimir . . . let us play a co-operative game.” Total, the French energy group, bought a 10 per cent stake in Russia’s $25.5bn Arctic LNG 2 project soon after, and last month opened a new oil blending plant close to Moscow.

The UK is one of the most hawkish towards Moscow, but British energy group BP is one of Russia’s biggest foreign investors through its 19.75 per cent stake in Rosneft, the Kremlin-controlled oil company subject to sanctions.

“Look at Total, piling in as much as it can. Look at BP,” says a senior executive at a major international energy company. “You cannot isolate a country as big and as important as Russia. It was never going to work.”

At a conference in Verona last month, Italy’s deputy prime minister Matteo Salvini told Russian delegates they were “peacemakers” and urged Italian companies to find ways around EU sanctions. “In 2018 we do not need sanctions, we do not need troops. We need dialogue, we need friendship,” he said. “I want to thank Italian businessmen . . . for resisting, for taking up the initiative with this.”

Western diplomats in Moscow privately admit that the sanctions have failed to achieve the impact many of their governments had desired.

Some blame the staggered implementation that has largely allowed Russia’s $1.6tn economy to slowly adjust. Others argue that the recovery in oil and commodity prices since 2016 has provided the Kremlin with enough cash to offset the impact. But others claim that many countries have lacked the resolve to follow through with the measures, fearing damage to their own companies.

Germany’s Daimler is building a factory close to Moscow that will start producing Mercedes-Benz E-Class sedans early next year. US aerospace giant Boeing opened a production plant in central Russia this summer to manufacture titanium components. Europe is buying more gas from Russia than at any time in history.

All the activity suggests that for company executives, Russia is too large and lucrative to let politics get in the way.

“There is something vitally important in the role of businessmen and policymakers continuing a dialogue,” Bob Dudley, BP’s chief executive, said at the Verona conference. “More and more there is a great importance that business plays in bringing the world closer. There are a lot of forces trying to push us apart.”

Since sanctions were first imposed on Rosneft in 2014, BP’s stake in the company has earned Rbs90.7bn ($1.3bn) in dividends, according to information on the Russian company’s website. “It is very difficult to remain in business for a long time by taking sides . . . we try to build bridges,” Mr Dudley added.

Compared with 2014, Rosneft has doubled the amount of oil it produces from joint projects with foreign companies to 1.4m barrels a day, thanks to partnerships with Norwegian, Vietnamese and Indian groups.

Washington’s use of international sanctions against Moscow only forces third countries to distance themselves from the US.

“It is pretty clear from where we sit that by trying to isolate Russia, America is doing a good job of isolating itself,” says one Asian diplomat in Moscow who declined to be named. “Even the Europeans are developing their own independent Russia policy.”

Boosted by new oil supply deals, agriculture and defence shipments, trade with China accounted for 15.5 per cent of Russia’s total turnover last year, up from 10.6 per cent in 2013. At the same time, the EU’s share fell from 49.6 per cent to 43.8 per cent.

With Saudi Arabia, too, the S-400 deal has come as part of a wider diplomatic and trade push. Moscow and Riyadh joined forces in 2016 to regulate oil production and drive up crude prices.

Saudi Aramco, the kingdom’s state oil producer, is keen to follow Total’s lead and buy a 30 per cent stake in the same gas project, and is also in talks to set up a petrochemicals plant with Russian company Sibur.

Regardless of their impact, western sanctions will probably continue for the medium term at least. The Democratic party’s victory in the House of Representatives last week has increased the chance of passing draft legislation imposing more restrictions on Russian banks and sovereign debt.

Washington in September imposed sanctions on China’s military for the S-400 purchases, prompting a fierce rebuke from Beijing. It also warned India, Saudi Arabia and Turkey that they too could face consequences for buying the systems.

Undeterred, Indian prime minister Narendra Modi welcomed Mr Putin in New Delhi last month with a hug, and the $5bn deal was signed.

“We will continue to closely follow the trends of the global arms market, and to offer our partners new flexible, convenient forms of co-operation,” Mr Putin told a meeting of his commission on foreign arms sales.

He added: “This is all the more important in the current conditions, when our competitors often resort to unscrupulous methods of struggle: they try to crush and blackmail our customers, including through the use of political sanctions.”