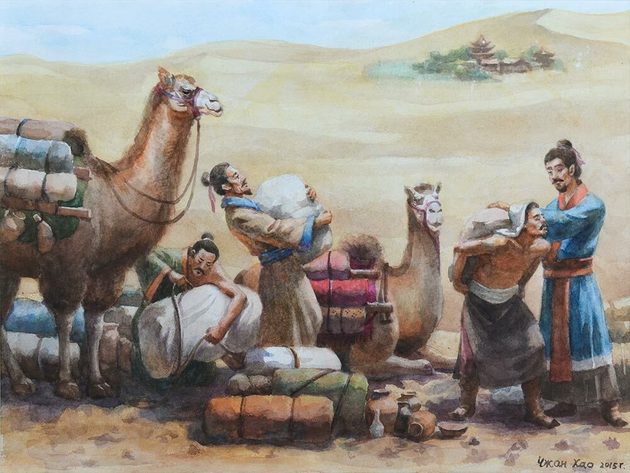

The vibrant network opened up exchanges between far-flung cultures throughout central Eurasia. The Silk Road wasn’t a single route, but rather a vibrant trade network that crisscrossed central Eurasia for centuries, bringing far-flung cultures into contact. Traveling by camel and horseback, merchants, nomads, missionaries, warriors and diplomats not only exchanged exotic goods, but transferred knowledge, technology, medicine and religious beliefs that reshaped ancient civilizations, The History writes.

The term “silk road” was coined in 1877 by Ferdinand Freiherr von Richthofen, a German geographer, who focused on the flourishing silk trade between the Chinese Han Empire (206 B.C. to 220 A.C.) and Rome. But modern scholars recognize that the Silk Road (or Silk Roads) continued to enable cross-continental trade until large-scale maritime trade replaced overland caravans in the 17th and 18th centuries.

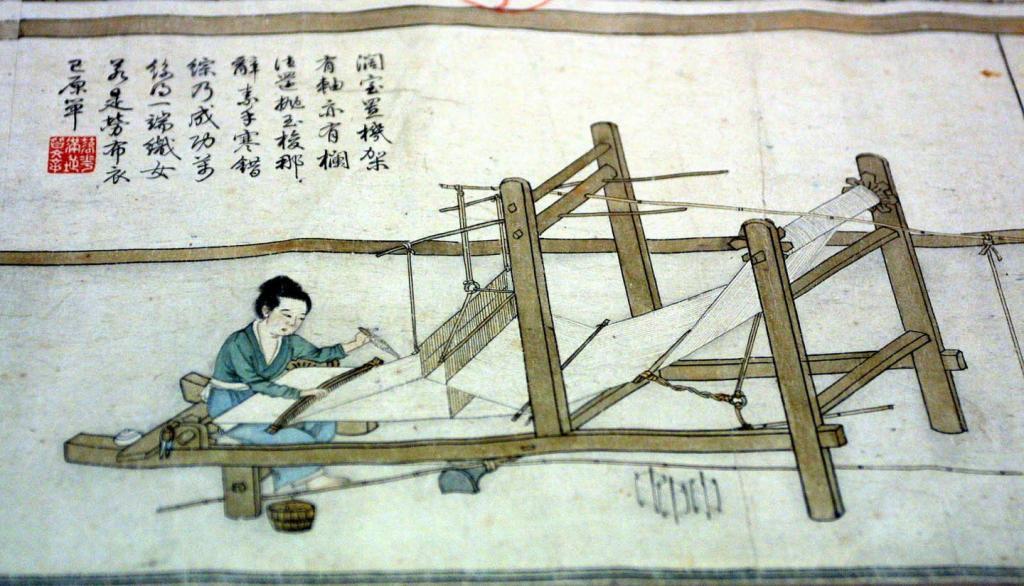

1. Silk

It’s called the Silk Road for a reason. Silk, first produced in China as early as 3,000 B.C., was the ideal overland trade item for merchant and diplomatic caravans that may have traveled thousands of miles to reach their destinations, says Xin Wen, a historian of medieval China and Inner Asia at Princeton University. “Your carrying capacity was very limited, so you brought whatever was most valuable, but also the lightest,” says Wen, whose upcoming book is titled The King’s Road: Diplomatic Travelers and the Making of the Silk Road in Eastern Eurasia, 850–1000. “Not only does silk fit these characteristics exactly—high value, low weight—but it’s also extremely versatile.”

The Roman elite prized Chinese silk as a luxuriously thin textile, and later, when silk-making technology was brought to the Mediterranean, artisans in Damascus created the reversible woven silk textile known as damask.

But silk was more than clothing, says Wen. In Buddhist cultures it was made into ritual banners or used as a canvas for paintings. In the important Silk Road settlement of Turfan in Eastern China, silk was used as currency, writes historian Valerie Hansen, and in the Tang Dynasty (618 to 907 A.C.), silk was collected as a form of tax.

2. Horses

Horses were first domesticated in the steppes of Central Asia around 3700 B.C. and transported nomadic tribes that hunted and raided across vast territories that bordered China, India, Persia and the Mediterranean. Once the horse was introduced into agrarian societies, it became a sought-after tool for transport, cultivation and cavalry, writes historian James Millward in Silk Road: A Very Short Introduction. The silk-for-horse trade was one of the most important and long-lasting exchanges on the Silk Road. Chinese merchants and officials traded bolts of silk for well-bred horses from the Mongolian steppes and Tibetan plateau. In turn, nomad elites prized the silk for the status it conferred or the additional goods it could buy.

Wen says that horses, by providing their own transportation, were the ultimate high-value, low-weight commodity on the Silk Road, and were “a very unique luxury item for the elite of the Eurasian world.” It’s not surprising that the famous tomb of the Chinese emperor Qin Shi Huang (259–210 B.C.) not only contains 8,000 terra cotta warriors, but also lifelike statues of 520 chariot horses and 150 cavalry horses.

3. Paper

Paper, invented in China in the second century A.C., first spread throughout Asia with the dissemination of Buddhism. In 751, paper was introduced to the Islamic world when Arab forces clashed with the Tang Dynasty at the Battle of Talas. The Caliph Harun al-Rashid built a paper mill in Baghdad that introduced paper-making to Egypt, North Africa and Spain, where paper finally reached Europe in the 12th and 13th centuries, writes Millward.

On the Silk Road, travelers carried paper documents that served as passports to cross nomadic lands or spend the night at a caravansary, a Silk Road oasis. But the most important function of paper along the Silk Road was that it was bound into texts and books that transmitted entirely new systems of thought, especially religion.

“It’s not a coincidence that Buddhism spread to China around the same time that paper became prevalent in the region,” says Wen. “Same with Manichaeism and Zoroastrianism. One of the central significances of the Silk Road is that it served as a channel for the spread of different ideas and cultural interactions, and much of that relied on paper.”

4. Spices

Spices from East and South Asia, like cinnamon from Sri Lanka and cassia from China, were exotic and coveted trade items, but they didn’t typically travel the overland routes of the Silk Road. Instead, spices were mainly transported along an ancient maritime Silk Road that linked port cities from Indonesia westward through India and the Arabian Peninsula.

Across the Silk Road, spices were valued for their use in cooking, but also for religious ceremonies and as medicine. And unlike silk, which could be produced wherever silk worms could be kept alive, many spices were derived from plants that only grew in very specific environments. “That means there’s a clearer origin for spice than for some of the other luxury items, which adds to their value,” says Wen.

5. Jade

Millennia before there was such a thing as the Silk Road, China traded with its western neighbors along the so-called Jade Road. Jade, the crystalline-green gemstone, was central to Chinese ritual culture. When jade supplies ran low in the 5th millennium B.C., it was necessary for China to establish trade relations with western neighbors like the ancient Iranian Kingdom of Khotan, whose rivers were rich with hunks of nephrite jade, the best variety of jade for carving intricate figurines and jewelry. The jade trade to China flourished throughout the Silk Road period, as did trade in other semi-precious gems like pearls.

6. Glassware

Westerners often assume that most Silk Road goods traveled from the exotic Far East westward to the Mediterranean and Europe, but Silk Road trade went in all directions. For example, archeologists excavating burial mounds in China, Korea, Thailand and the Philippines have found Roman glassware among the prized possessions of the Asian elite. The distinct type of soda-lime glass made in Rome and fashioned into vases and goblets would have eagerly been traded for silk, which Romans were obsessed with.

7. Furs

The taiga is the vast stretch of evergreen forest that runs through Siberia in Eurasia and continues into Canada in North America. In the days of the Silk Road, writes Millward, the taiga attracted hardy bands of trappers who harvested fox, sable, mink, beaver and ermine pelts. This northern “fur road” supplied luxurious coats and hats to Chinese dynasties and other Eurasian elites. Millward writes that Genghis Khan cemented one of his earliest political alliances with a gift of a sable coat. By the 17th century, in the waning days of the Silk Road, rulers from the Chinese Qing Dynasty could buy furs from both Siberian and Canadian trappers.

8. Slaves

Enslaved people were a tragically common “trade good” along the Silk Road. Raiding armies would take captives and sell them to private traders who would find buyers in far-flung ports and capitals from Dublin in the West to Shandong in Eastern China, writes Silk Road historian Susan Whitfield. The slaves became servants, entertainers and eunuchs for royal courts. Wen says that while enslavement was pervasive in premodern Eurasia along the Silk Road, none of these kingdoms or societies could be classified as “slave-based” in the same way that the African slave trade operated in the New World. “Slaves were more like an ornament of the life of the Silk Road elite,” says Wen, “Not a major economic source.”